The contract that pays for empty beds

Across the United States, an unsettling contract clause has quietly shaped the business model of private prisons: the occupancy guarantee. Under these clauses, governments promise to keep a contracted facility filled to a certain percentage (often 80–100%). If the government fails to deliver that number of detainees or inmates, it must still pay the company for the empty beds. That arrangement converts declines in incarceration—whether from reforms, fewer arrests, or changing enforcement priorities—into a line item governments may be forced to pay for anyway.

Lawsuits and settlements: real dollars, real consequences

When governments cannot meet those occupancy thresholds, private companies have sometimes turned to the courts. One of the most widely discussed examples involved Management & Training Corporation (MTC) and a facility in Arizona that had an extremely high occupancy guarantee. After the state failed to meet the contractual quota, MTC sought millions in lost-revenue claims; the dispute later ended in a settlement rather than a protracted court fight. That episode has become shorthand for the perverse incentives such contracts create.

These legal actions are not mere corporate posturing. The potential liability from a single occupancy guarantee can add up to millions of dollars, turning what might otherwise be a policy discussion about reducing incarceration into a financial calculation that pressures local and state governments.

Why occupancy guarantees matter for policy

Occupancy guarantees distort public policy in at least two dangerous ways:

-

They financially penalize reductions in incarceration. If a county or state moves to shrink its prison population—for example, by expanding diversion programs, shortening sentences for low-level offenses, or decriminalizing certain behaviors—the government can still owe private operators for unfilled beds. That makes reform more costly on paper and complicates budgeting choices.

-

They create lobbying leverage. Private operators have a financial stake in maintaining high incarceration levels. When contracts are written to guarantee payment regardless of population, the companies have less incentive to support rehabilitation and more incentive to protect bed usage—creating a conflict between profit motives and public safety or rehabilitation goals.

A pattern across states and counties

Analyses of private-prison contracts show that occupancy guarantees are common. Investigations and contract reviews by advocacy groups and legal analysts have found many agreements requiring governments to pay for a large share of beds even when they go unused. The practical result is that taxpayer money can subsidize empty capacity—money that otherwise might support social services, education, or reentry programs.

Recent reporting and public records have shown multiple disputes and threats of litigation in jurisdictions that attempted to reduce reliance on privatized detention or that experienced sudden population declines. In several places, local governments faced tough choices: pay millions to private operators, renegotiate at loss, or defend their stance in court.

Broader legal and ethical questions

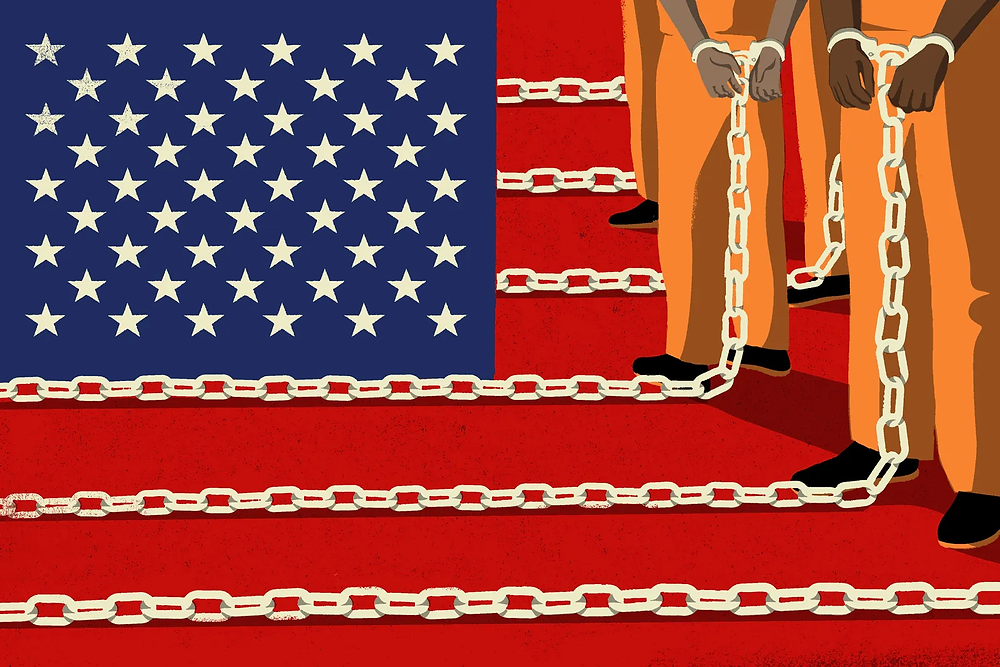

Beyond the fiscal hit, occupancy guarantees raise fundamental ethical questions about the privatization of punishment. If profit depends on volume—if empty beds trigger payouts—then incarceration becomes a revenue stream rather than a correctional measure aimed at public safety or rehabilitation. Critics argue that this model treats people as assets on a balance sheet and can undermine efforts to implement humane, community-based alternatives. The debate increasingly frames occupancy clauses not just as poor contracting, but as a structural driver of mass incarceration incentives.

Recent developments and government scrutiny

The private-prison industry has been under closer scrutiny in recent years—not only for occupancy clauses but also for facility conditions, staffing, and relationships with federal agencies. Separate investigations and federal inquiries into private operators have highlighted problems ranging from understaffing to alleged civil-rights violations at some facilities, adding political pressure to reexamine how contracts are structured and whether privatization is in the public interest. These broader concerns feed into how courts, legislatures, and the public assess disputes over occupancy clauses and contract enforcement.

What this means for Black and marginalized communities

Because Black people are disproportionately represented in the U.S. justice system, the financial incentives created by occupancy guarantees have a racialized impact. Policies or contracts that make it costly to reduce incarceration indirectly affect Black communities more—by sustaining higher jail and prison populations, by diverting public funds from social supports, and by slowing reforms aimed at reducing racial disparities in the criminal-legal system.

Taxpayer dollars spent to pay for unused prison capacity represent a missed opportunity: those resources could strengthen schools, housing, mental health services, or reentry programs—investments that evidence suggests reduce crime and improve community outcomes.

Moving forward: policy options and accountability

There are practical steps governments and advocates can pursue to prevent occupancy guarantees from undermining reform:

-

Reject or remove occupancy guarantees from new contracts. Jurisdictions can refuse to sign contracts that lock them into paying for empty beds.

-

Include performance incentives that align with public-safety goals. Contracts can be redesigned to reward outcomes such as reduced recidivism, successful reentry, or improved facility conditions—rather than bed counts.

-

Increase contract transparency. Making contract terms public enables oversight, informed debate, and accountability.

-

Pursue alternative detention models. Invest in community-based supervision, diversion, treatment programs, and housing stability—options that reduce reliance on incarceration.

-

Legal and legislative reform. Where contracts already exist, legislatures and courts can weigh the public interest in renegotiation, enforcement, or new rules governing private corrections.

Conclusion: When the business model fights reform

The emergence of lawsuits by private prison companies over empty beds is more than a legal quirk: it reveals how contractual structures can embed incentives at odds with public safety, justice, and racial equity. For communities striving to reduce mass incarceration and reinvest in people, occupancy guarantees are a practical and moral obstacle. Undoing them will take political will, contractual savvy, and community pressure to ensure that justice isn’t priced by corporate balance sheets.

Amazing how privatizing government institutions and services always leads to theft. Gota feed those starving Billionaires somehow or other. Hence privatization is Snap Benefits for rich people.

So true.

BRAVO!!! Great article.